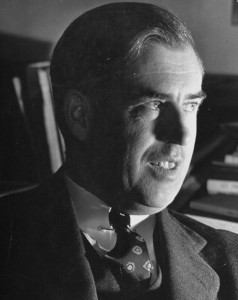

Wallace, Henry Agard (1888-1965)

Henry Wallace

An American government and political leader who was Secretary of Agriculture in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal administration (from 1933 to 1940), Roosevelt’s second Vice President (from 1941 to 1944), Secretary of Commerce (from 1945 to 1946) and a third-party presidential candidate in 1948.

Henry Wallace was born on October 7, 1888 in a frame farmhouse near the town of Orient, Iowa, into a family of farmers turned publishers. His father, Harry Wallace, was the son of the Reverend Henry Wallace, who by 1888 was the publisher of the largest local newspaper and the editor of Iowa’s most influential farm journal. His mother – a deeply religious woman, brought up by a strict Methodist aunt – was a strong influence upon her son. Young Henry Wallace grew up in a home where idealistic notions of service to one’s fellow man were valued more than the pursuit of personal wealth and power. The Wallaces’ attitude toward farming was a mixture of religion, a sense of duty and a scientific pursuit. In 1892, the family relocated to Ames, Iowa so the father could complete his education at Iowa State College. In late 1893, Harry Wallace earned his bachelor’s degree and was appointed associate professor of dairying at Iowa State. Soon, he founded a semi-monthly, Farm and Dairy, and invited his father, Henry Wallace, to become its editor. Eventually, the paper developed into an influential journal, which advocated the application of science to agriculture, in addition to efficient planning and management.

In 1910, the younger Wallace graduated from Iowa State College, where he studied plant genetics and crossbreeding. He discovered and patented a hybrid corn that was more productive and disease-resistant than normal corn. This achievement allowed the young Wallace to found his own business to manufacture and distribute the plants, a venture that gave him valuable experience for his later career in public service. The communal society of turn-of-the-century Iowa, with its agrarian lifestyle, made a life-long impact upon Wallace’s values, particularly the idealism which is usually associated with his name.

Eventually, Wallace went to work for the family paper, then called Wallaces’ Farmer, and in the early 1920s he became its publisher after his father became Secretary of agriculture in the administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. The Wallaces were long-standing Republicans, but the younger Wallace broke with his father’s party in 1928 over the issue of farm relief and high tariffs. That same year he campaigned for the Democratic candidate, Alfred E. Smith, in the presidential elections. This brought Wallace to the attention of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was urged by Smith to run for governor of New York in 1928. In 1932, Wallace supported Roosevelt in the latter’s bid for the presidency. When Roosevelt became president, he appointed Henry A. Wallace to be his Secretary of Agriculture on March 4, 1933.

An idealist and intellectual, Wallace proved to be an efficient administrator as well. At the height of the Great Depression, he launched an activist farm program to limit production, subsidize growers and raise prices – and gradually implemented government planning in the farm belt. Determined to preserve the rural way of life, Wallace at the same time saw farming as a business and worked to make it profitable through a combination of New Deal programs, including the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), the Farm Credit Administration, the Rural Electrification Administration, the Soil Conservation Service, the food stamp and school lunch programs, etc. He also managed to turn the Department of Agriculture into one of the largest government departments, and it came to be considered the best-managed department during the New Deal years. With his long-term interest in agricultural science, Wallace also significantly expanded his department’s scientific programs. Its research center at Beltsville, Maryland came to be regarded as the largest agricultural station in the world.

In the words of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., “Wallace was a great secretary of agriculture. In 1933 a quarter of the American people still lived on farms, and agricultural policy was a matter of high political and economic significance. … Today, as a result of the agricultural revolution that in so many respects Wallace pioneered, fewer than 2% of Americans are employed in farm occupations – and they produce more than their grandfathers produced 70 years ago.” 1

With time, Wallace’s liberal agenda expanded to include concern for the situation of labor and the urban poor, as well as for the growing threat from Nazi Germany, fascist Italy and Japan. By the late 1930s, he had become an outspoken internationalist and a true Rooseveltian liberal. In 1940, posing America’s hard choice between the economy of Hitler’s New Order, America’s traditional unregulated system and the alternative regulated economy of the New Deal, Wallace argued: “Freedom in a grown-up world is different from freedom in a pioneer world. As a nation grows and matures, the traffic inevitably gets denser, and you need more traffic lights.” 2 An original thinker and a prolific writer, during the years of the Great Depression Wallace was, in the words of John Kenneth Galbraith, “second only to Roosevelt as the most important figure of the New Deal.” 3

This explains Roosevelt’s choice of Wallace as his running mate when he decided to run for an unprecedented presidential third term in 1940. By that time, Wallace had a formidable following among the liberals, farmers, labor and minorities who made up the New Deal voting block – and looked like a logical presidential successor. Faced with resistance from the leadership of the Democratic Party, which saw Wallace as too idealistic and lacking the supporters needed to balance the ticket, Roosevelt threatened to drop out of the race – and ultimately won Wallace’s nomination as vice-presidential candidate.

As vice president, Wallace was the leading spokesman for American liberalism and increasingly an advocate of the idea that the world war should usher in a new era, which he called the “Century of the Common Man”: “I say that the century on which we are entering—the century which will come out of this war—can be and must be the century of the common man.” 4 Wallace was an early advocate of the creation of a permanent United Nations organization. On December 28, 1942, in a radio address on the 86th anniversary of the birth of President Woodrow Wilson, Wallace said: “The task of our generation—the generation which President Roosevelt once said has a ‘rendezvous with destiny’—is so to organize human affairs that no Adolf Hitler, no power-hungry warmongers, whatever their nationality, can ever again plunge the whole world into war and bloodshed.” Speaking before Detroit labor leaders on July 25, 1943, he urged that the goals of the New Deal must be taken up again – both in the United States and internationally.

In early 1944, speaking about his vision for post-war America, Wallace addressed the hopes of rank-and-file Americans and warned “the Big Three—Big Business, Big Labor and Big Agriculture”— that “if they struggle to grab federal power for monopolistic purposes [they] are certain to come into serious conflict unless they recognize the superior claims of the general welfare of the common man.” To realize these claims, Wallace saw a need for “the maximum use of all our resources in the service of the general welfare.” 5

Despite Wallace’s articulate commitment to Roosevelt’s vision for a better world, in 1944, when choosing the running mate for his fourth presidential campaign, Roosevelt bent to the strong opposition to Wallace among the Democratic Party leadership – probably to avoid the risk of division within the party. Although deeply disappointed, Wallace nevertheless accepted Roosevelt’s offer to become his Secretary of Commerce. Following Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945, Wallace continued as Secretary of Commerce for President Harry Truman until the fall of the next year, when Truman dismissed Wallace after the latter’s September 12, 1946, speech at Madison Square Garden. In that speech, Wallace publicly voiced his opposition to Truman’s increasingly tough approach to the Soviet Union. 6

After his resignation as Secretary of Commerce on September 20, 1946, Wallace soon became the editor of the New Republic magazine. With the first winds of the Cold War, he quickly became one of the most prominent critics of American foreign policy and the course Soviet-American relations had taken since President Roosevelt’s death. In his crusade for change in U.S. policies, Wallace crossed paths with a nationwide organization, the Progressive Citizens of America, formed in December 1946. By late 1947, when Wallace decided that the only way to effect change in America was to run for president on an independent ticket, the Progressive Citizens of America began moving toward becoming a third party.

The party was launched in Philadelphia at the National Founding Convention of the New Party on July 23 -25, 1948. It adopted the name the Progressive Party and nominated Wallace for president. In his acceptance speech, Wallace made the case for the Democratic Party’s betrayal of the ideals of the New Deal. “In marched the generals—and out went the men … who had planned social security and built Federal housing, the men who had dug the farmer out of the dust bowl and the workman out of the sweatshop.” 7

Wallace visits the Soviet Embassy with his wife and daughter, May 1945

The party was endorsed by the CPUSA and counted a number of secret Communists among its founders, the members of its National Committee and Wallace’s advisors and speechwriters. The party’s ticket included universal government health insurance and civil rights; it opposed the Berlin airlift and blamed the United States for the Communist conquest of Czechoslovakia. Judging from memos and profiles in the Russian files from the late 1940s to the early 1950s, the American Communists had covertly “played a decisive role in the organization of the party and have extended to it their complete support,” but considered Wallace to be their “temporary ally.” In the Soviet view, the Progressive Party was “a bourgeois party of a liberal direction.” 8 Despite the behind-the-scenes Communist influence and the continuous interest on the part of the Soviets, who saw Wallace as a political figure the “progressive forces” could rally around, in the Soviet-era files he does not look like a “tool of Moscow.” This frequent charge during the 1948 campaign cost Wallace votes even among his expected constituency. It is difficult to say whether Wallace was naive in not noticing the Communists’ role in his party – or whether he, too, saw the Communists as his ‘temporary allies.’ Wallace’s dream soured at the polls, where he received only a little more than 2% of the votes nationwide.

The presidential campaign of 1948 became the final act in Wallace’s political life, after which he began gradually drifting into political obscurity. The Molotov Papers collection in Moscow contains a once-secret TASS report from February 26, 1950 on Wallace’s speech at the Progressive Party convention – heavy with Molotov’s pencil marks. Molotov’s pencil stopped at the words, “We must fight for God and for America, … to save America from a false Prussian concept that ‘Force is law.’ We are not Prussians. We are not materialists, we are Americans.” 9 In the summer of 1950, Wallace walked out on the party over the issue of the war in Korea. In 1952, he published, Where I Was Wrong, describing his reversal on leftist politics. By that time, he had retired to his experimental farm in upstate New York – to return to the experimental farming and agricultural science of his youth. In the 1956 presidential election Wallace voted for Eisenhower, the Republican candidate – but he was enthusiastic about the election of Democrat John F. Kennedy in 1960. He died on November 18, 1965.

Watch for alerts on this website to read more about Henry A. Wallace’s appearances in Soviet files.

- “Who Was Henry A. Wallace? The Story of a Perplexing and Indomitably Naïve Public Servant,” by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Los Angeles Times, March 12, 2000. ↩

- Henry A. Wallace, The American Choice (1940), Cit. the Henry A. Wallace Center for Agricultural and Environmental Policy, http://newdeal.feri.org/wallace/docs.htm ↩

- Cit., ““Second Only to Roosevelt,” Henry A. Wallace and the New Deal,” Selected Works of Henry A. Wallace, New Deal Network, http://newdeal.feri.org/wallace/index.htm ↩

- “The Price of Free World Victory,” a speech delivered to the Free World Association, New York City, May 8, 1942, The Henry A. Wallace Center for Agricultural and Environmental Policy, Op. cit. ↩

- “World Organization,” speech delivered by radio on the 86th anniversary of Woodrow Wilson’s birth, December 28, 1942; “America Tomorrow,” speech delivered in Detroit on July 25, 1943; “What America Wants,” speech delivered in Los Angeles on Friday, February 4, 1944; “America Can Get It,” speech delivered in Seattle on Wednesday, February 9, 1944, Ibidem. ↩

- “The Way to Peace,” speech delivered before a meeting under the joint auspices of the National Citizens Political Action Committee and the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions, New York, N.Y., September 12, 1946, Ibidem. ↩

- “My Commitments,” Progressive Party Candidate for President of the United States Acceptance Speech, Philadelphia, Pa., July, 24, 1948, Ibidem. ↩

- V. Grigoryan to V.M. Molotov, December 18, 1950, a memo on the situation in the Progressive Party of the USA, Fund 82 (the Molotov Papers), description 2, file 1325, pp. 220-223, RGASPI, Moscow. ↩

- TASS (Secret), February 26, 1950, fund 82, description 2, file 1325, pp. 44-46. ↩