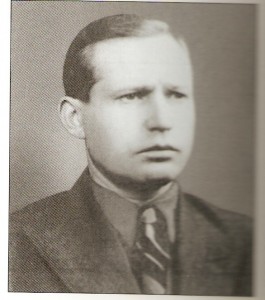

Sergeev, Lev Alexandrovich (1906-1994)

An officer of the Soviet strategic military intelligence (GRU), who served as its resident in Washington, D.C. from March 1940 to January 1946.

Sergeev was born on November 14, 1906 in the little town of Zakataly, in Azerbajdzhan (then part of the Russian Empire), according to his brief official biography, into a poor Russian peasant family. However, some of the revealing biographical details suggest that he was the son of an officer in the Russian Army who committed suicide when Sergeev was only three years old. The family was indeed very poor – with the mother struggling to raise two small children with no means. Sergeev began earning his living in 1920, working at odd manual jobs, and managed to finish secondary school (which at that time comprised seven grades) only in 1926. In 1924, he joined the Young Communist Alliance (commonly known as Comsomol) and became an active member of that organization. In 1929, Sergeev enrolled at a Red Army medical orderly school in Tbilisi – and began his Red Army service that same year. In 1930-1931, he served as a medical orderly for an artillery regiment; and, from 1931 to 1933, he was a first sergeant at the medical orderly school where he had formerly trained. In 1930, he joined the Communist party (VCP (b)). In 1933, he enrolled at the armored troops’ officer school in Orel, from which he graduated in 1936. After his graduation, he continued serving at that school as a platoon commander.

In 1937, Sergeev was selected for service at the Red Army Intelligence Directorate (known as Razvedupr) and was sent to Moscow. From April 1937 to July 1938, he worked on individual assignments. In August 1938, he was assigned as a secretary at Razvedupr – and in May 1939, was promoted to the position of senior assistant to the head of the division that supervised operations in the United States. As of October 1939, Sergeev’s rank was only that of Senior Lieutenant. However, in early 1940, he was selected for an important assignment: to become the Razvedupr’s resident in Washington, D.C., working under deep cover as a driver for the Soviet military attaché. Initially, Sergeev’s task was to recruit agents for work in Nazi Germany. However, a few months after he was posted to Washington, D.C., his assignment changed to obtaining information in the United States on Nazi Germany and Japan, as well as other information that would facilitate the Soviet leadership’s understanding of American foreign policy in Europe and the Far East.

By September 1941, the organizational phase of Sergeev’s group was completed – and the group was assigned a code name, “Omega.” By that time, Sergeev’s cover had changed to that of a clerk at the Soviet military attaché’s office – and he came to work under an operational pseudonym, “Moris.” In 1942, Sergeev was promoted to the rank of Captain – and by the end of World War II, he was a Major. At its height in 1944, the group included seven important sources in Washington, D.C. as well as two operatives whom the GRU Moscow Centre dispatched to assist Sergeev. The latter turned out to be a talented spymaster who conducted his operations in the most covert way. For instance, he never met with his sources in person, but rather relied upon a “cut-out” – a professionally trained agent-group leader with the operational pseudonym “Doctor,” who maintained contact with the sources and performed other organizational tasks.

Sergeev’s name was publicly revealed for the first time in 1995 by the late Colonel-General Anatoly Pavlov, a former first assistant head of the GRU and a long-time chairman of its veterans’ association. 1 In 2003, Sergeev’s brief bio appeared in a reference book on the GRU 2

Lota’s account included a few archival citations on the most important information obtained by “Moris.” According to Lota, Sergeev’s efforts provided the Soviet Commander-in-Chief Joseph Stalin with timely information “to help him take correct [military] decisions.” For instance, in later part of 1941, Sergeev sent a few reports on the most vital issue of the day for Stalin, assuring him that “Japan would stay out of the war.” In the fall of 1941, reinforced by similar reports from Richard Sorge, the famous GRU agent in Japan, Sergeev’s dispatches helped Stalin to make a difficult decision – namely, to relocate the Red Army’s Siberian divisions to Moscow, an action which turned out to be a decisive factor in the Soviet Union’s thwarting of Nazi plans for a blitzkrieg against the USSR.

In early 2009, a new account of Sergeev and his “Omega” group was published by a Russian military journalist, Mikhail Boltunov, a Colonel and the editor-in-chief of the official magazine published by the Russian Department of Defense. 3 Colonel Boltunov’s 2009 account does not include discussion of the documentary information provided by the “Omega” group; however, it looks more accurate in biographical and organizational detail than Lota’s account.

In Colonel Boltunov’s estimate, Sergeev’s “Omega” group, “without doubt, was the best station ["rezidentura"] of the [Soviet] military strategic intelligence of the World War II period – to judge by [such criteria as] efficiency, the volume and value of informational materials, as well as the continuity and timing of the delivery [of materials] to the Centre.” 4 In the accounts of both Russian military writers, Lota and Boltunov, this rave review received substantial confirmation. Both Lota and Boltunov write that on February 22, 1945, Sergeev received congratulations from the head of the GRU, with high Soviet government awards to his agent group leader and sources: three Orders of Lenin, one Order of the Red Banner, one “Badge of Honor” Order and one medal “For Merit in Combat”. 5 Sergeev and his operatives got their awards on September 1, 1945. Sergeev, then holding the rank of Major, was awarded the Order of Lenin – and his assistants, the Order of Patriotic War and the Red Star Order.

Both writers describe Sergeev as a talented and able spymaster with a brilliant “combinational” mind, strong problem-solving abilities and superb operational talents. In particular, they credit Sergeev with state-of-the-art tradecraft in conducting his covert operations, a capability which saved Sergeev himself, his operatives and his sources from being spotted by American counterintelligence. In addition, both writers independently maintain that not a single one of Sergeev’s sources was compromised. 6

Sergeev returned to Moscow in January 1946. For his American mission, besides the Order of Lenin, he was awarded two Orders of the Red Banner, two orders of the Red Star and a medal “For Victory over Germany.” He continued his work at GRU headquarters and was eventually promoted to the rank of Colonel, but sent into retirement in 1960 at the age of 54. He died in Moscow in 1994. As he had no heirs after the death of his wife of more than 50 years, he willed his apartment and belongings to the GRU.

- A.G. Pavlov, “Sovetskaja voennaja razvedka nakanune velikoi otechestvennoi voiny.” – Novaja i noveishaja istorija, 1995, No. 1, ss. 27-30. (A.G. Pavlov, “Soviet Military Intelligence on the Eve of the Great Patriotic War.” – The Modern and Contemporary History, 1995, No. 1, pp. 27-30); A.G. Pavlov, “Voennaja razvedka SSSR, v 1941-1945 gg.” – Ibid., 1995, No. 2, ss. 48-59 ( “The Military Intelligence of the USSR in 1941-1945,” by A.G. Pavlov, Ibid., 1995, No. 2, pp. 48-59.) ↩

- V. M. Lurie and V. Ya. Kochik, GRU: Dela i ljudi, Moskva: Olma-press, 2003, p.464 (GRU: Deeds and People, by V.M. Lurie and V.Ya. Kochik, Moscow: Olma-Press, 2003, p.464.) Since 2005, the story of Sergeev and his “Omega” group has been promoted by a Russian chronicler of the GRU Vladimir Lota, who obviously enjoyed access to some of the GRU’s records. [[3. Vladimir Lota, “”Ramzai”, “Moris” i “Dora” protiv Ribbentropa,” Sekretnyi front General’nogo shtaba, Moskva: Molodaja gvardija, 2005, ss. 237-256 (“‘Ramzai’, ‘Moris’ and ‘Dora’ Against Ribbenthrop,” in The Secret Front of the General Staff, by Vladimir Lota, Moscow: Molodaya Guardia, 2005, pp. 237-256; Vladimir Lota, “MORIS vykhodit na svjaz,’” Krasnaja Zvezda, 5 maja 2006. (“MORIS Gets on Air,” by Vladimir Lota in Red Star, May 5, 2006); Vladimir Lota, “Na svjaz’ vykhodit ‘Moris,’” Za granju vozmozhnogo: Voennaja razvedka Rossii na Dal’nem Vostoke, 1918-1945 gg., Moskva: Kuchkovo Pole, 2008, ss. 342-389 (” ‘Moris’ Gets on Air,” in Beyond the Possible: Russian Military Intelligence in the Far East, 1918-1945, by Vladimir Lota, Moscow: Kuchkovo pole, 2008, pp. 342-389. ↩

- “Nash chelovek v Vashingtone,” – Mikhail Boltunov, Razvedchiki, izmenivshie mir, Moskva: Algoritm, 2009, s. 109. (“Our Man in Washington,” in The Intelligence Officers Who Changed the World, by Mikhail Boltunov, Moscow: Algorythm, 2009, p. 109. ↩

- Ibid., p. 137. ↩

- “MORIS Gets on for a Contact,” by Vladimir Lota, Op. Cit.; Mikhail Boltunov, Op. Cit., p. 137-138. ↩

- Vladimir Lota uses the expression “ne popal v pole zrenija,” translated verbatim as “did not get into the view,” with regard to American counterintelligence. Colonel Boltunov, when queried as to his sources for a similar statement, said that he saw one in Sergeev’s biographical reference – and, besides, had heard the same thing from Sergeev’s close friends, whom Boltunov interviewed over the years. All of them reportedly said that Sergeev had told them (at different periods of time, beginning after his return to Moscow from his American mission and up to the early 1990s) that he considered the greatest achievement of his mission his ability to avoid compromising any of his sources. ↩